Think of

stories in the Bible which involve food.

What happens

when food is eaten and what happens afterwards?

Think of

what happens in a meal you have shared recently, during the meal and after it.

“Why

have we made something Jesus made so simple and transferable, so complicated?”

In Acts the

emerging church is regulation light (no mention of the apostles presiding at

the breaking of bread) - Also noteworthy is the context “they broke bread at

home.”

Note the

distinction between home and Temple in Acts

2: 46. The Lord’s Supper was inaugurated where? In the upper room of a home

by Jesus who was born in Bethlehem which means “house of bread.” The

discipleship meal began in an everyday, domestic context, sacred in its

simplicity, transferable and transcultural, accessible to all.

The breaking

of bread is a term Luke uses elsewhere. See Luke 24: 35 - where is Jesus known by Cleopas and his companion?

What is happening here? An everyday event infused with sacred significance. A

holy habit to be practiced with due reverence for the one who instituted it,

anytime, anyplace, anywhere? Whenever believers are together they can break bread

as part of the meal as well as part of an act of worship, and not just remember

but experience the risen Jesus in the midst of their fellowship. An ordinary

meal and the Eucharist blended together. Acts

27: 35 – meal that Paul shared with the sailors began with Paul giving

thanks and breaking bread. Encouraged and renewed spiritually they were then

nourished and strengthened physically as they ate together.

The breaking

of bread should made you feel better.

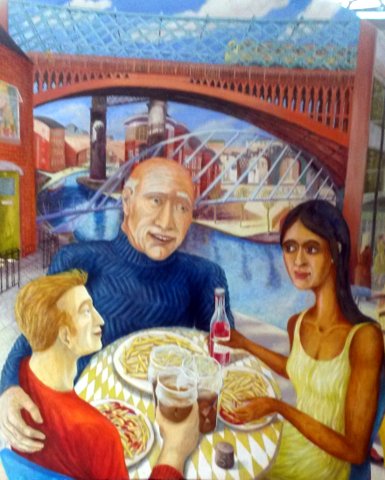

The last

meal I shared was at the River Haven carvery in Rye, with folk from the church

but also my former colleague in Stamford and Rutland Circuit Malcolm Peach, and

his wife Heather. Malcolm has retired to Canterbury and comes over to lead

worship in the east of the Circuit to help me out. What did we do yesterday? As

well as taking time over the food (how many meals do we rush? My Granny used to

tell me to masticate each piece of food 30 times) and enjoying it, we caught up

with life and our stories, we heard about future plans for us all, we told

stories of the past which made us laugh, we gave thanks for the meal at the end

and for the time, we went away nourished and refreshed.

Breaking of bread is rooted in

thanksgiving.

Jewish meal rituals – prayers that reflect a

deep dependence and thankfulness to God who provided for all needs, physical

and spiritual.

Jewish

spirituality – everything you do calls you to remember and thank God. Would not

think of eating or drinking without first saying the appropriate grace or

benediction. Saying of grace for us? Still done? Or not?

This prayer pattern

shines through the New Testament – Colossians

3: 17. Best known Jewish thanksgiving of all is the Last Supper benediction

of Jesus “when he had given thanks” over the bread and the cup.

Every action,

every moment of the day, was related to the gracious God who protected and

provided for the dependent community.

Last Supper

rooted in Jewish thanksgiving spirituality

Think

about the last time you shared in a communion service – have we examples of

times and places we have received and the event has changed us? Is it a

renewing thing? Do we remind ourselves of a past event, that happens still

today and that God is in control? What happens for you as you go to the rail or

the bread is given to you in your seat and you eat together as we are doing on

Sunday mornings at St Helens at the moment because we haven’t room to come to

the front? We wait and eat together as a community. Plenary after (10 minutes)

Both

Jesus and Paul regarded the sharing of meals as means of breaking down barriers

and building up relationships.

Jesus ate

and drank with sinners (Mark 2: 15f)

The parable

of the prodigal son (Luke 15: 23 – 24,

32) ends with an invitation to a meal of joy and reconciliation.

See earliest

account of Last Supper in bible – 1

Corinthians 11: 17 - 34

Again, see

it in a Jewish context as a structure – remember Christians weren’t suddenly

invented when Jesus came – Jesus was a Jew and first followers were Jews so

knew Judaism. Basic features of a formal Jewish meal are in the account. Head

of the household would say a blessing to God at the beginning, bread would be

broken and shared, and at the end of the meal, thanks would be offered for the

cup of blessing.

Interesting

though, meal is not in a Jewish context in Corinthian Church – cosmopolitan

city. Some people think setting here was a symposium, a drinking gathering

after a supper, with a special cup of wine dedicated to a special god,

(recorded in Plato), which led to other activities – philosophical discussions,

games, sex, religious discussion, a time of social interaction. Not a solemn

affair. Church has this background, this sort of meal, so open to abuse. So, if it is to unite – Paul gets cross hence

-

Conversely,

greedy or inconsiderate behaviour at the Lord’s Supper could break the church’s

fellowship and unity symbolised among other things by the one loaf and the

common cup (1 Corinthians 11: 17 – 34)

Not greed,

all given the same, no matter who we are. Prayer of Humble Access – see service

book, and invitation to communion in Lenten service – really beautiful.

Some

group work using ideas on how we break bread together:

The breaking of bread as missional

tool

Rev Barbara

Glasson was stationed some years ago to city centre Liverpool. She writes:

‘A city centre is a wonderful mixing pot – and on my

first day I took the train to town and just looked around,’ Being only five

foot two, Barbara felt dwarfed by the huge buildings – but also intimidated by the size of the task if the Gospel was to impact

Liverpool city centre.

Her thoughts

turned to yeast – something tiny which can make a huge difference in baking. An

idea began to form in her mind which she thought might be from God. So she invited

accountant Andrew Loveday to go for a

walk with her, near Albert Dock.

‘What do you

think about baking bread?’ she asked him.

They found

some rooms to rent above a radical left wing bookshop, got an oven, gathered a

few friends together and started pummelling dough – at first carefully

following the directions on the flour packet,

as none of them had any experience of baking bread.

‘We made a

huge mound of loaves. For every one we

kept for ourselves we committed to giving one away.’

People who

received a delicious free freshly baked loaf asked why. And the next time the group gathered to make

bread some of those who had been given loaves were there to join in.

Bread-making is fun, it’s sociable and friendly.

A small

community evolved, very naturally, around the regular bread-making times. While

the bread was rising, the conversation would turn to the important issues of

life, shared in the warm kitchen. People would read from the Bible, pray for

one another. They became companions (=

cum panis, with bread).

Some of

those who were given free bread and who were drawn into the group came from the homeless street-dwellers of the big city.

‘We try to be a place where people can be warm,

safe and who they are, around the bread.’

‘Making bread has taught us so much – the process

of baking mirrors so much in life: the pummelling and proving is about how we engage

with one another, the waiting for the dough to rise is about how we give each

other time. Churches generally are a bit obsessed with numbers and outcomes. But the bread makes

us wait … it needs to rest, to rise. In the waiting time the smell of the bread

triggers memories and facilitates story so that people quite naturally talk to

each other. And every loaf we make is different. Bread is a sign to the world.

‘We bake at least

twice a week. We have a faith development meeting one evening, and we meet to

worship on a Sunday. We’ve had weddings, blessings, baptisms and even one funeral.’

On Friday,

while away, I visited the coffee shop in what was our Circuit church in

Stamford, Lincolnshire, and was told about Second Helpings.

Second

Helpings is a community café, established to intercept perfectly good food that

would otherwise go to waste.

The café is

run by a team of volunteers who aim to turn the rescued food into delicious,

nutritious meals that are available to all diners on a Pay-As-You-Feel basis – the

choice people have is to donate whatever value you feel your food was worth and

this can be in the form of money or time.

Adam Smith:

founder of the Real Junk Food project:

"It is

bringing people from different demographics together that doesn't involve

money. People are opening Junk Food Projects because they have had enough of

what is going on in society and care about what is happening to other human

beings," It is a revolution."

"We

cook the basics in the cafe because many people don’t know how to do the basic

things with food," he said. "I know people who think they don’t know

how to make a fruit salad and they are 40-years-old. They didn’t get it was

just chopping up fruit and putting it into a bowl. We have realised there is a

serious lack of basic education in the UK in terms of food awareness, what to

make and where it comes from. "We cook basis sides, sauces, stews, casseroles,

cakes, to get people eating this sort of food again and it is so easy to make "We regularly take food from supermarket bins if we have

to," he said. "We watch them throw it away, then we go and take it

back out again 10 minutes later. Over 90% of the goods are perfectly

fine."

This is sacramental breaking of bread in a new way!

Think about what

we have done to the breaking of bread by rules. Does it matter to you who gives

you the bread at communion? Have we

always had an open table and are you happy

we have? (Wasn’t always so, communion was done behind the wall at the

end of Sunday School) One church I served, three quarters of them didn’t take

the communion despite sharing the liturgy? Why do you think that was so? Have

we made something so simple too complicated?

Breaking of bread as transformative act

Does sharing

bread change us?

Read story

of Inderjit Bhogal and the man he gave bread to…

At his

induction as President of Conference in 2000 he spoke of what he finds

compelling in Jesus Christ: how Jesus expresses a God who is with us all, who

respects people of other faiths and who eats with whoever will eat with him; a

man who dies abandoned by his friends. "The genius of Jesus was to put

food, a meal, at the centre of his community."

"To

embrace each other is to accept each other without requiring everyone to think

and speak and appear the same To embrace is to be prepared to sit at Table

together and share bread with others.”

Perhaps

someone needs to share this with President Trump…

A final

quote:

“ “There are people in the world so hungry,

that God cannot appear to them except in the form of bread.”

― Mahatma

Gandhi

Sharing a

piece of bread given by another

How do we

become a bread church, overflowing with generosity, sharing with those who are

hungry today? Is breaking of bread the heart of the Gospel?